Tomorrow marks the end of the first quarter of the year. Businesses will determine if they have met their quarterly goals and will check their progress toward their annual goals. It is a good time for individuals to do the same.

If you made any New Year’s resolutions, how have you done with them? If you are like most people, your resolution has already failed, likely some time ago. New Year’s resolutions have a terrible track record. Their success rate is only 8% according to one often-cited study. There are several reasons for this.

For one, people often resolve to make behavioral changes, such as changing their diets, starting an exercise program, or quitting smoking. Behavioral changes are notoriously difficult, in part because they involve changing habits. Some studies of habits suggest it takes 21 or 30 days of consistent activity to form a new habit (or break an old one), and some studies even suggest it takes two months or longer for a new habit to take hold. So in this regard, it is not surprising that New Year’s resolutions often fail.

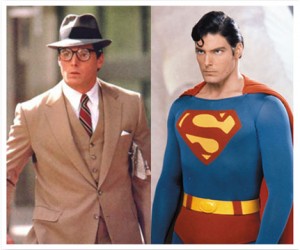

[pullshow id=h1]But there is another reason why resolutions have such a poor success rate of enacting change. It is because they are resolutions. [pullthis id=h1]Resolutions are a form of a promise. A promise is kept, or a promise is broken. It is a binary function. One cannot have partial success in keeping a promise.[/pullthis]

In contrast, goals are a direction, something to move toward. One can reach a goal, as one can keep a promise (or resolution). But one can also make progress toward a goal. Can one make progress toward a resolution? Also there can be setbacks on the way to a goal, and that’s OK. But once a promise has been broken, it is broken. For example: one resolves to quit smoking. The smoker stops smoking for 3 weeks. Then he lights up. If he had made a New Year’s resolution to quit smoking, his resolution has failed. It’s all over. If it were his goal to quit smoking, he would have suffered a setback, but he could continue in his efforts to quit. He has already made progress toward the goal, in that he had not smoked for 3 weeks, then he can try again to make further progress, perhaps quitting for 6 weeks or longer next time.

[pullshow id=h2]This difference is not merely semantic, it is psychological. [pullthis id=h2]The resolution-maker who suffers the setback is likely to give up, having “failed” to keep the resolution. In contrast, the goal-setter is less likely to give up, as the goal is still the intended destination no matter if the path toward it turns out to be more circuitous than initially expected.[/pullthis] And the resolution-maker has little opportunity for positive feedback until the end of the year. But the goal-setter is rewarded psychologically with partial successes all along the way. “I lost my first pound, hooray!” is a reasonable feeling from one who has a goal of losing 30 pounds. One who has a resolution to lose weight is unlikely to celebrate incremental progress this way.

If you declared resolutions for behavior change this year, it would be advisable to revise them into goals. This will increase your chance to succeed in the making the desired change.